This is Part 4 of our A/Fuel Dragster Tech Series. We started off with an introduction to injected nitro racing. In Part 2, you saw the crazy intake and fuel systems on the Fuel Hemi cars, and Part 3 revealed the short-block and cam specs. Now it’s time to dive into the clutch of an NHRA A/Fuel Dragster with help from the team of Veale and Brown Motorsports.

Since these cars do not utilize a transmission, you may be wondering how they transmit the massive amount of power the engine makes to the rear wheels. The simple answer is that the cars use a clutch, but it certainly is nothing like the one in your hot rod.

The clutch uses multiple friction discs and floaters to create a pack that operates with varying amounts of slippage throughout the run, until it ultimately locks up nearing the end of a pass. Tuning this mechanical marvel is at the heart of the duties of a crew chief. Figuring out how to apply several thousand horsepower without causing the tires to smoke, or bogging down the motor, is part artistry, part science, and part black magic. Done correctly, record numbers show up on the score board. Miss the setup and your car is smoking the tires less than 50 feet into a run.

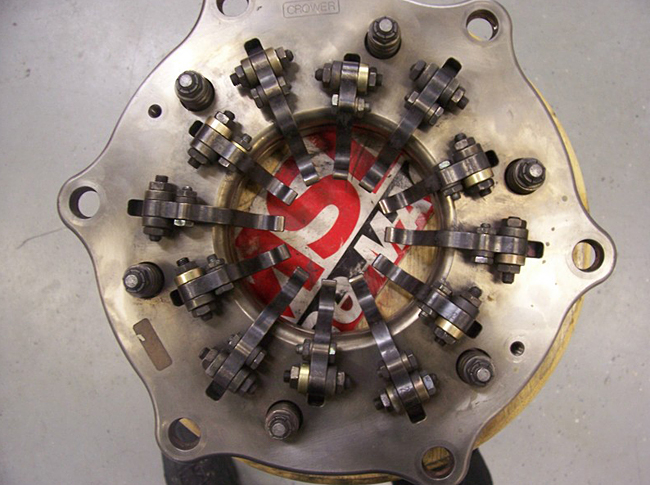

The clutch pack consists of four clutch discs and three floaters. Each run sees one new disc and three seasoned discs in the pack. Discs can be ordered with varying Rockwell hardness ratings which equate to different friction levels and affect the setup.

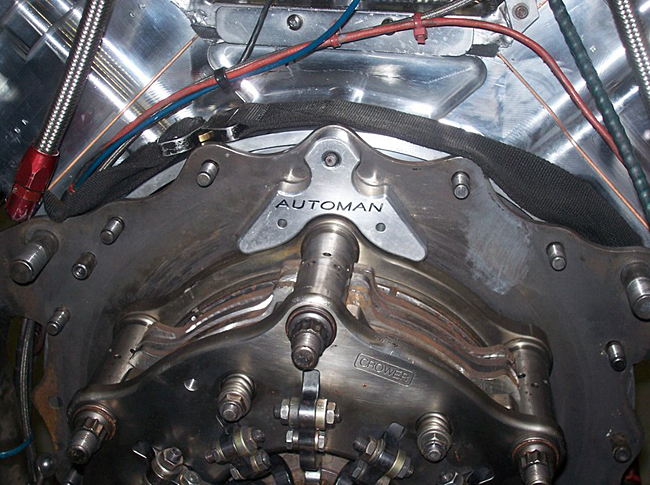

The clutch is activated by the rpm of the engine. It’s, at base, a massive centrifugal clutch. Brown runs a Crower unit in his car. The clutch has six stands and 12 levers. The levers are what actually cause the clamping force and are tuned by adding or subtracting weights.

As the clutch spins, the weights are forced out against the pressure plate compressing the clutch and causing the car to apply more power to the rear wheels. Aside from the fingers there are also pneumatic timers that, at different points in the run, allow the discs of the clutch to contact each other more and more, aiding the secondary fingers in causing the unit to lock up.

It is not uncommon for a clutch in a Top Fuel or A/Fuel car to actually weld itself together by the end of a run. In fact, even after the car gets to the pits, the discs and floaters are so hot the technician servicing it has to wear asbestos gloves to pull the unit apart.

The guys typically have the clutch set so that when the driver hits the throttle to launch the car, the motor will hit 5,000 rpm before it engages enough to actually launch the dragster off the starting line. Adding weight to the fingers means that the clutch will engage at a lower rpm on the initial hit of the throttle whereas lightening them will allow the motor to wing up higher before engaging. The previously mentioned pneumatic timers are activated by a microswitch that is engaged by the throttle. Once you hit the pedal, the timers start running, and if all goes well, the clutch will fully lock around 1,000 feet.

While all this is going on, the crew chief also has had to figure out how much fuel to feed the motor. When there is little load on the engine the mix is comparably lean, but as the clutch is engaged, more and more fuel is fed to the motor.

There are a myriad of factors that a crew chief has to consider when getting the clutch setup correct. Say the fuel pump is rated at 58 gallons per minute at 8,000 rpm.

Here’s the mental conversation that happens in the event the crewchief wants to deliver 27 GPM to the engine at 5,000 rpm.

Take 58 GPM the pump is rated for and divide it by 8,000. Now multiply it by the new initial hit rpm of 5,000. That equals 36.25 GPM. At this point the crew cheif neeeds to pull 9 GPM to get down to the 27 GPM he wants. If the engine only went to 4,800 rpm and smoked the tires, they could take 20 grams of weight off the clutch (tp change how hard and soon the car “hits” the tire, or reduce of 7 GPM (58/8000 X 4800 =34.8 — 27 = 7.8 GPM). If it smoked the tires, he’d take maybe 5 degrees of timing out and try it again.

That may have been incomprehensible to you, but it gives you at least some idea about the decisions a crew chief is making when setting the car up for the next lap. Most races are won and lost in the clutch can on these and most other high-powered drag race machinery. The guy who can best manage the slippage, fuel flow, launch RPM, lock up point, and every other detail is the guy who holds the trophy over his head on Sunday afternoon.

Man, we love this stuff.